Logo. The face of branding

¿Cuál es el concepto del logo de Quito?

El concepto se basó en un estudio que fue contratado a una empresa española, la misma que concluyó que, “la ciudad tenía baja autoestima”. Aunque los habitantes de Quito aman su ciudad y están muy orgullosos de ella, la relación entre la Ciudad y los ciudadanos era casi inexistente. A pesar de que Quito es la capital más alta del mundo (2850 m / 9,350 pies sobre el nivel del mar), no nos sentimos exactamente en la cima del mundo. Decidimos enfocar la comunicación en la idea de “ascender”, como una característica visual que generaría impulso para ascender, para crecer. A nivel técnico, la Ciudad nunca había tenido una marca que fuera capaz de mediar sus comunicaciones y ordenar su marco institucional. La comunicación fue diversa y no estuvo guiada por un estándar corporativo. El símbolo del Municipio es el escudo de armas de la ciudad, que fue diseñado durante la época colonial, como una ciudad española en los Andes. Al mismo tiempo, ha utilizado numerosos logotipos sin alcanzar nunca un aspecto corporativo. Asimismo, el Municipio cuenta con 97 instituciones, y cada una de ellas tenía su propia imagen, lo que generó poca visibilidad institucional.

¿Qué tipo de letra es?

Swiss 721, diseñado por Max Medinger, un tipógrafo suizo que trabajó en el desarrollo de la tipografía Helvetica en 1957. Esta tipografía fue seleccionada casi 3 años antes de firmar el contrato para la imagen de la ciudad como parte del diseño del sistema de señalización turística y peatonal del distrito histórico de Quito. Algunas de las direcciones del proyecto de Quito se establecieron durante este proyecto. La tipografía, al igual que otros elementos de comunicación, como la combinación de colores, las formas simples, la verticalidad, fueron el modelo para el futuro proyecto de imagen de la Ciudad.

¿Por qué los colores rojo y azul?

Son los colores de la bandera de la ciudad. Los habitantes de Quito tienen una mentalidad muy tradicional y la bandera está en las calles, por ley en los feriados y días cívicos. Los colores de la bandera son la única paleta cromática.

Nuestra propuesta fue aplicar el mismo logo con una extensión tipográfica de las siglas de cada institución como acrónimo. De esta forma se redujo la cantidad de mensajes y se impuso la marca QUITO.

¿Qué tan complicado es tratar con un cliente gubernamental? ¿Cuánto tiempo tomó? ¿Cómo estuvo?

Lamentablemente, en Ecuador, un proyecto de esta magnitud no es entendido por las autoridades como una herramienta para orientar el comportamiento de los ciudadanos, que guía, protege, promueve e informa a los habitantes de la ciudad. En cambio, se aborda el tema desde un ángulo político y electoral para asegurar el poder. Cada nueva administración elimina la imagen anterior como símbolo de disputa política. Fue necesario hacer una presentación sobre el alcance de la marca para que el Alcalde y su equipo aprobaran la propuesta. La imagen fue diseñada para durar al menos 25 años. Se convocó a tres estudios de diseño gráfico que ya habían trabajado para la Ciudad. Los diseñadores convocados fueron Belén Mena, Silvio y Sandro Giorgi del Estudio Giotto, y yo, Pablo Iturralde, del Estudio Anima. Al salir de la reunión decidimos hacer el proyecto juntos y compartir la ganancia.

¿Diseñaste el ícono del Patrimonio de la Humanidad de la UNESCO?

No, fue diseñado por Michel Olyff, un diseñador gráfico belga, específicamente para el nombramiento de Quito y Cracovia (Polonia) como Patrimonio Cultural de la Humanidad en 1978.

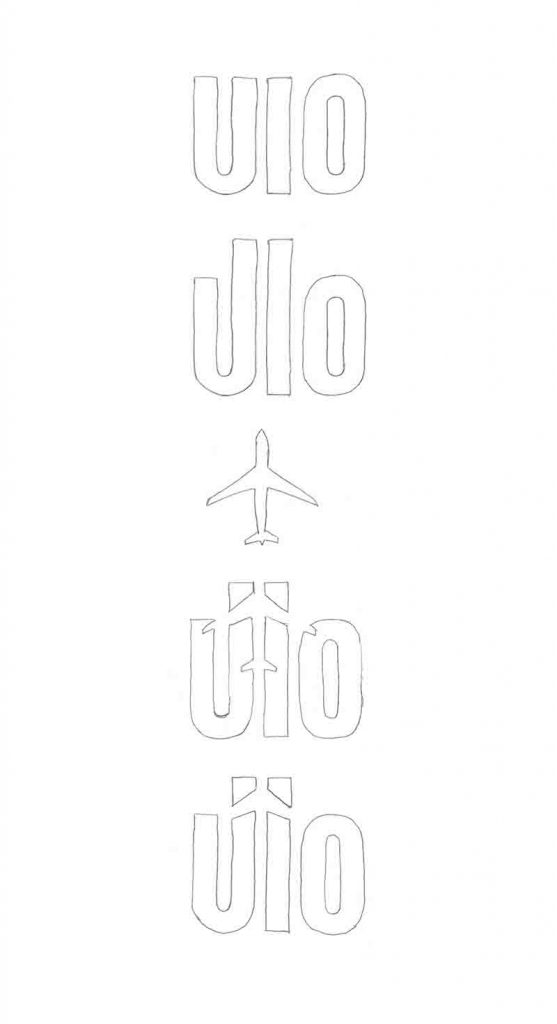

El logo del Aeropuerto parece una extensión del logo de Quito y funciona perfectamente. ¿Cuánto tiempo te llevó llegar a eso? ¿Cuántas opciones hiciste?

De hecho, es una extensión de la marca. Además de la tipografía y el color, resuelve de manera diferente el tema constante de “subir”, que en este caso es vertical, además de reforzar el código aeroportuario de Quito, UIO. La imagen del aeropuerto de Quito no estaba en la oferta inicial. Cuando terminamos de diseñar la imagen de Quito, pudimos dedicar un tiempo a diseñar la marca del futuro aeropuerto de la ciudad. Para entonces ya se hablaba de la ubicación proyectada para el nuevo aeropuerto las afueras de la ciudad, donde se iba a construir lo que hoy se llama el Aeropuerto Internacional Mariscal Sucre en Tababela, Quito. El proceso de diseño tomó un par de días y no fue necesario pensar mucho en el problema. Siempre me sentí atraído por el código del aeropuerto de la ciudad, así que intenté incluir la imagen de un avión en la parte superior del logo y eso fue todo. Cuando el siguiente alcalde cambió, la imagen de la ciudad, fue retirada también la del aeropuerto y reemplazada por otra diferente. Esa administración duró casi 4 años y, cuando terminó, la Administración del Aeropuerto me llamó para retomar el logotipo. Las autoridades deben comprender que los procesos de diseño no pueden permitir interferencias de carácter político. La Ciudad, concebida desde su identidad visual, debe ser considerada muy por encima del clima político, y debe avanzar en sus soluciones a partir de lo permanente y estable en la identidad de su gente.

¿Cuál es la función del logotipo actual? ¿Ha cambiado desde el pasado?

Creo que el papel del logo siempre será el mismo: intentar establecer visualmente un discurso que sea equivalente al contenido de la oferta (el servicio, mensaje o producto), y que permita identificarlo y reconocerlo. eso. Si esto se logra, y el lenguaje también es coherente dentro del contexto cultural, el usuario establece una conexión con la marca. Hoy en día, hay más canales de comunicación y la marca necesita adaptarse a los nuevos medios. Al mismo tiempo, la tecnología ha permitido reducir drásticamente el tiempo de producción. Por otro lado, la aparición de cientos y miles de agencias de publicidad que ofrecen “el mismo producto” que un diseñador o un estudio de diseño, pero a mitad de precio, deterioran la situación. Creo que los editores de escritorio de algunas agencias de publicidad no deberían llamarse diseñadores gráficos sino operadores gráficos. Es importante entender que el diseñador es la persona que toma las decisiones y tiene la última palabra, algo que no sucede en una agencia de publicidad. Sumado a esto, en las universidades latinoamericanas, el currículo favorece la preparación en aplicaciones de diseño o en materias teóricas, ofreciendo a los estudiantes mucho conocimiento de “dibujo digital”, pero poco criterio sobre comunicación visual. Entre los sistemas que sobrevivieron al vaivén político de la ciudad, el más importante en términos de consecuencia internacional es el Sistema de Señalización Publicitaria Exterior, que debía generar una solución al problema de la señalización comercial en una de las zonas más activas y vibrantes. centros urbanos comerciales de América Latina. El problema radica en que las antiguas casonas del centro histórico de Quito, que pertenecían a las familias acomodadas del antiguo Quito, ahora son pequeños complejos comerciales que albergan hasta 20 negocios diferentes en una misma casa. El espacio promocional de sus marcas era, por necesidad, la pared de la puerta de entrada. Esto generó una contaminación visual brutal porque cada letrero competía con los demás letreros a su alrededor, y la ciudad vieja se escondía detrás de miles de letreros. La solución planteada en este proyecto fue diseñar los carteles con letras de hierro negro (Swiss 721) ancladas a la pared. Esta solución es ahora un estándar para la ordenación comercial en varias ciudades latinoamericanas con distritos históricos similares.

What is the concept for the Quito logo?

The concept was based on a study that was hired to a Spanish company, which concluded that, “the city had low self-esteem”. Although the inhabitants of Quito love their city and are very proud of it, the relationship between the City and the citizens was almost nonexistent. Despite the fact that Quito is the highest capital in the world (9,350 ft above sea level), we didn’t feel exactly on top of the world. We decided to focus the communications on the idea of “moving up”, as a visual feature that would generate momentum to move upward, to grow.

At the technical level, the City had never had a brand that was able to mediate its communications and order its institutional framework. The communications were diverse and they were not lead by a corporate standard. The symbol of the Municipality is the coat of arms of the city, which was designed during the colonial era, as a Spanish city in the Andes. At the same time, it has used numerous logos without ever attaining a corporate look. Also, the Municipality has 97 institutions, and each one of them had its own image, which generated little institutional visibility.

What is the typeface?

Swiss 721, designed by Max Medinger, a Swiss typographer who worked on the development of the Helvetica typeface in 1957.

This typeface was selected almost 3 years before signing the contract for the image of the city as part of the design for the tourism and pedestrian signage system for Quito’s historic district. Some of the directions for the Quito project were established during this project. The typeface, just like other communication elements, such as the color scheme, the simple forms, the verticality, were the model for the future image project for the City.

Why the red and blue colors?

They are the colors of the city Slag. The inhabitants of Quito are very traditional-minded and the Slag is in the streets, by law, on holidays. The colors of the Slag were the only color scheme. Our proposal was to apply the same logo with a typographic extension of the assigned institution as an acronym. In this way, the amount of messages was reduced, and the Quito brand prevailed.

How complicated is it to deal with a governmental client? How long did it take? How was it?

Unfortunately, in Ecuador, a project of this magnitude is not understood by the authorities as a tool for directing the behavior of the citizens, which guides, protects, promotes and informs the city dwellers. Instead, it is approached from a political and electoral angle in order to secure power. Each new administration eliminates the previous image as a symbol of political dispute.

It was necessary to make a presentation on the scope of the brand to get the Mayor and his team to approve the proposal. The image was designed to last at least 25 years. Three graphic design studios that had already worked with the City were called. The designers who were called were Belén Mena, Silvio and Sandro Giorgi from Giotto Studio, and myself, Pablo Iturralde, from Anima Studio. When we left the meeting we decided to propose doing the project together and sharing the proSit.

Did you design the icon for the UNESCO World Heritage Site?

No, it was designed by Michel Olyff, a Belgian graphic designer, in 1978, speciSically for the naming of Quito and Cracovia (Poland) as World Cultural Heritage Sites in 1978.

The logo for the airport seems like an extension of the Quito logo and it works perfectly. How long did it take you to come up with that? How many options did you do?

It is, in fact, an extension of the brand. In addition to the typeface and the color, it resolves in a different way the constant theme of “moving up”, which is vertical in this instance, in addition to reinforcing the UIO airport code.

The image of Quito’s airport was not in the initial offer. When we Sinished developing the Quito image, we were able to devote some time to designing the brand of the future airport of the city. By then there was already talk of the new airport’s projected location outside of the city, and the new site was being prepared in the outskirts of town, where they were going to build what today is called the Mariscal Sucre International Airport in Tababela, Quito. The design process took a couple of days and it wasn’t necessary to brood over the problem very much. I always felt attracted by the airport code of the city, so I tried to include the image of an airplane to the top of the logo and that was it.

When the Mayor changed, the image of the city, together with that of the airport, was withdrawn and replaced by a different one. That administration lasted almost 4 years and, when it ended, the Airport Administration called me to retake the logo.

The authorities have to understand that design processes cannot allow interferences of a political nature. The City, as conceived from its visual identity, must be considered very much above the political climate, and it must advance its solutions based on what is permanent and stable in the identity of its people.

What is the function of today’s logo (with branding, etc.)? Has it changed from the past?

I think that the role of the logo will always be the same: to try to establish visually a discourse that is equivalent to the content of the offer (the service, message, or product), and that makes it possible to identify it and recognize it. If this is accomplished, and the language is also coherent within the cultural context, the user makes a connection with the brand.

Today, there are more communication channels, and the brand needs to adapt to new media. At the same time, technology has made it possible to drastically reduce production time. On the other hand, the emergence of hundreds and thousands of advertising agencies that offer “the same product” as a designer or a design studio, but at half the price, deteriorate the situation. I think the desktop publishers of some advertising agencies should not be called graphic designers but graphic operators. It is important to understand that the designer is the person who makes the decisions and has the last word —something that doesn’t happen in an advertising agency. In addition to this, in the Latin American universities, the curriculum favors preparation in design applications or on theoretical subjects, offering the students much knowledge of “digital drawing”, but little criteria on visual communication.

Among the systems that survived the political back and forth of the city, the most important one in terms of international consequence is the Exterior Advertisement Signage System, which had to generate a solution for the problem of commercial signage in one of the most active and vibrant commercial urban centers of Latin America. The problem lies in that the old large houses of Quito’s historic center, which belonged to the wealthy families of old Quito, are now small commercial complexes housing up to 20 different businesses in the same house. The promotional space for their brands was, by necessity, the wall at the gate entrance. This generated a brutal visual pollution because every sign competed with the other signs around it, and the old city was hidden behind thousands of signs. The solution put forth in this project was designing the signs with black iron letters (Swiss 721) anchored to the wall. This solution is now a standard for commercial ordinance in several Latin American cities with similar historic districts.

Hi, my name is Diego Vainesman. I own the design studio 40N47 Design, Inc. and I’ve been working in New York City for the past 30 years. I teach Typography at the Masters of Visual Narrative at the School of Visual Arts here in New York and I was the first latin president of the Type Directors Club.

In 2014 I was first invited to teach logo design workshops in Spain. Today, the list of countries has greatly expanded. The workshops have taken me to many cities: La Paz, Havana, Puebla, Buenos Aires, Valencia, Beijing, and many more. During those workshops the students are eager to learn everything about logos. Who designed it? Why did they design it a certain way? I was answering these questions from my own perspective. Until one day it dawned on me: How about I go straight to the designer or typographer who designed those logos and get the answers from them?

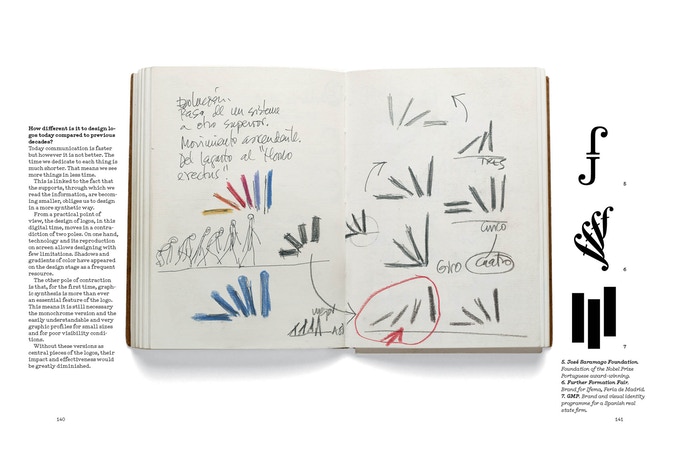

I know what you’re thinking. “Another book of logos? Who’s going to read it?”That was my first reaction. But this book not only emphasizes the thinking of the designer, but also their craft. I didn’t interview just logo designers but also also designers, typographers, artists, who also happen to design logos.

I also added some of my own questions to the mix in order to have a most comprehensive understanding of each logo.

This book emphasizes the thinking and sketching that goes into every logo. From the concept, to the vector that ends up on the screen. What are the stories behind these logos?

I hope you can help me get this book in the hands of designers and, more importantly, students. They deserve to have the real answers. Thank you!

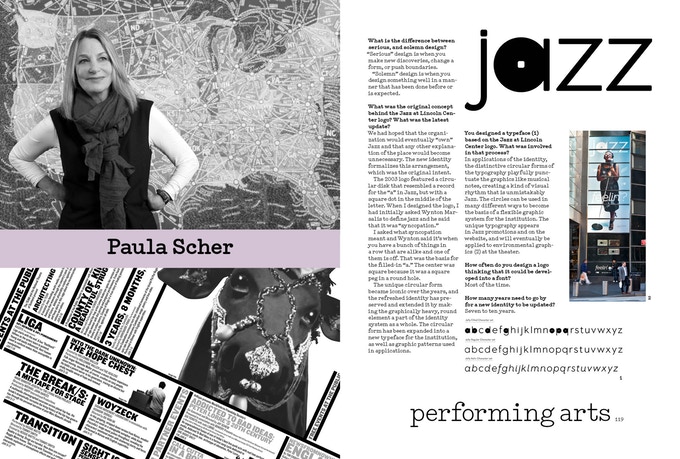

Meet the Designers

Matteo Bologna (Italy), Gerard Huerta (USA), Marina Willer (Brazil), Yetkin Başarir (Turkey), Roberto de Vicq de Cumptich (Brazil), Mario Eskenazi (Argentina), Gail Anderson (USA), Taku Satoh (Japan), Georgia Fendley (UK), Ed Benguiat (USA), Michalis Georgiou (Greece), Hubert Jocham (Germany), Susan Sellers (USA), Georgianna Stout (USA), Michael Rock (USA), Stefanidis Dimitris (Greece), Saki Mafundikwa (Zimbabwe), Elizabeth Carey Smith (USA), Pepe Gimeno (Spain), Neelakash Kshetrimayum (India), Christine Strohl (USA), Eric Strohl (USA), Gabriel Martínez Meave (Mexico), Yury Ostromentsky (Rusia), Nick Fasciano (USA), Jennifer Kinon (USA), Bobby Martin (USA), Ricardo Rousselot (Argentina), Pablo Iturralde (Ecuador), Yo Santosa (Indonesia), Mehdi Saeedi (Iran), Daniel Eatock (UK), Paula Scher (USA), Peter Mussfeldt (Germany), John Langdon (USA), Jakob Trollbäck (Sweden), Marieke Stolk (Netherlands), Erwin Brinkers (Netherlands), Danny van den Dungen (Netherlands), Manuel Estrada (Spain), Gemma O’Brien (Australia), Lance Wyman (USA), Rubén Fontana (Argentina), Louise Fili (USA), Nelson Ponce (Cuba), Marko Šesnić (Croatia), Goran Turković (Croatia), Andrea Sužnjević (Croatia), Jorge dos Reis (Portugal), and Zhao Liu (China).